Unlocking the Secrets of Longevity: How VO2 Max Influences Your Health

What is the impact of Vo2 Max and longevity?

The term Vo2 max was previously reserved for endurance buffs, elite athletes and sports scientists. More recently, it has entered the common vernacular because of the growing research linking it with a longer, healthier and more fulfilling life.

We have more control over our long-term health than previously understood, so how does Vo2 max impact your health?

Firstly, let's understand what it is and get clarity on terminology.

Cardio - Short for cardiorespiratory system. How blood, oxygen and other nutrients are transported around the body, primarily using the heart and lungs.

Aerobic - A system that creates energy in our body (Adenosine Triphosphate) using carbohydrates and fats in the presence of oxygen.

Vo2 Max - A measure of how much oxygen your body can consume in one minute. We commonly express it relative to an individual's body weight (e.g. mL/(kg.min)).

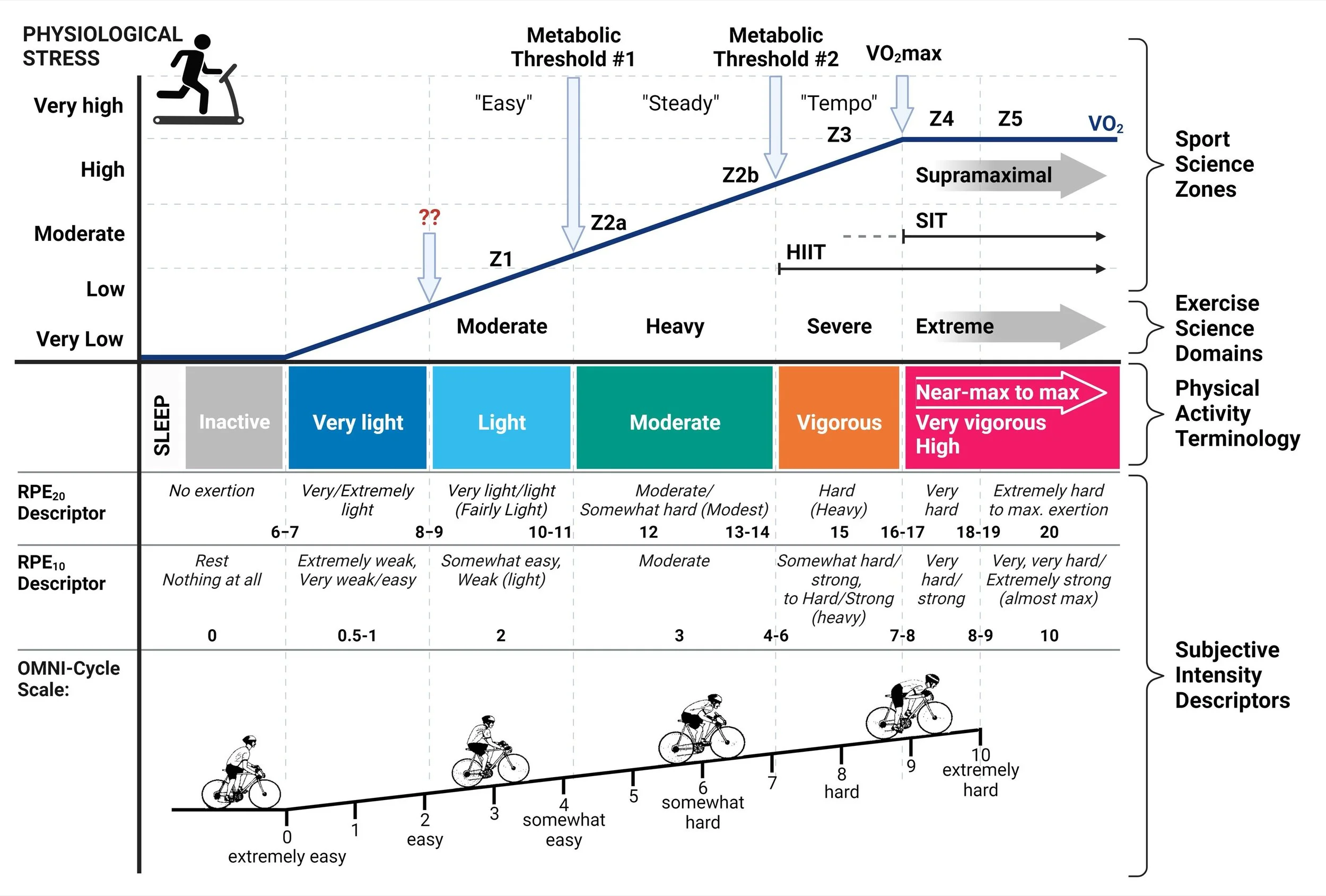

Zone 2 - This isn't highly relevant to this article. However, a day doesn't go by without it appearing on the internet. Zone 2 training is typically around 55-75% of Vo2 max or after the first metabolic threshold.

From this, you can see that zone 2 training can improve your aerobic energy system, which enhances your cardiorespiratory system, measured by a Vo2 Max test.

What happens when we age?

Vo2 max diminishes at a rate of 10% per decade after age 25 for men and around 7% for females. It's widely accepted that 80% of this decrease is attributed to your cardiac output. Cardiac output is the product of your heart rate and stroke volume. i.e. the frequency of heartbeats and amount of blood per beat. Since maximal heart rate declines steadily with age and is unchanged through training, stroke volume is the modifier in the equation.

How does this impact longevity?

At the morbid end of the spectrum, research has shown that a Vo2 max of 17.5 mL/(kg.min) is required for independent living. Suppose it drops to 11.5 mL/(kg.min), or less. In that case, the energy demands to remain alive require approximately 30% of your Vo2 max. This results in exhaustion from essential bodily functions and, ultimately, a natural death. Not good.

On the positive end, a high Vo2 max is inversely correlated with all-cause mortality. All-cause mortality is death due to disease complications or hazardous exposure, which includes cancer, heart disease, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

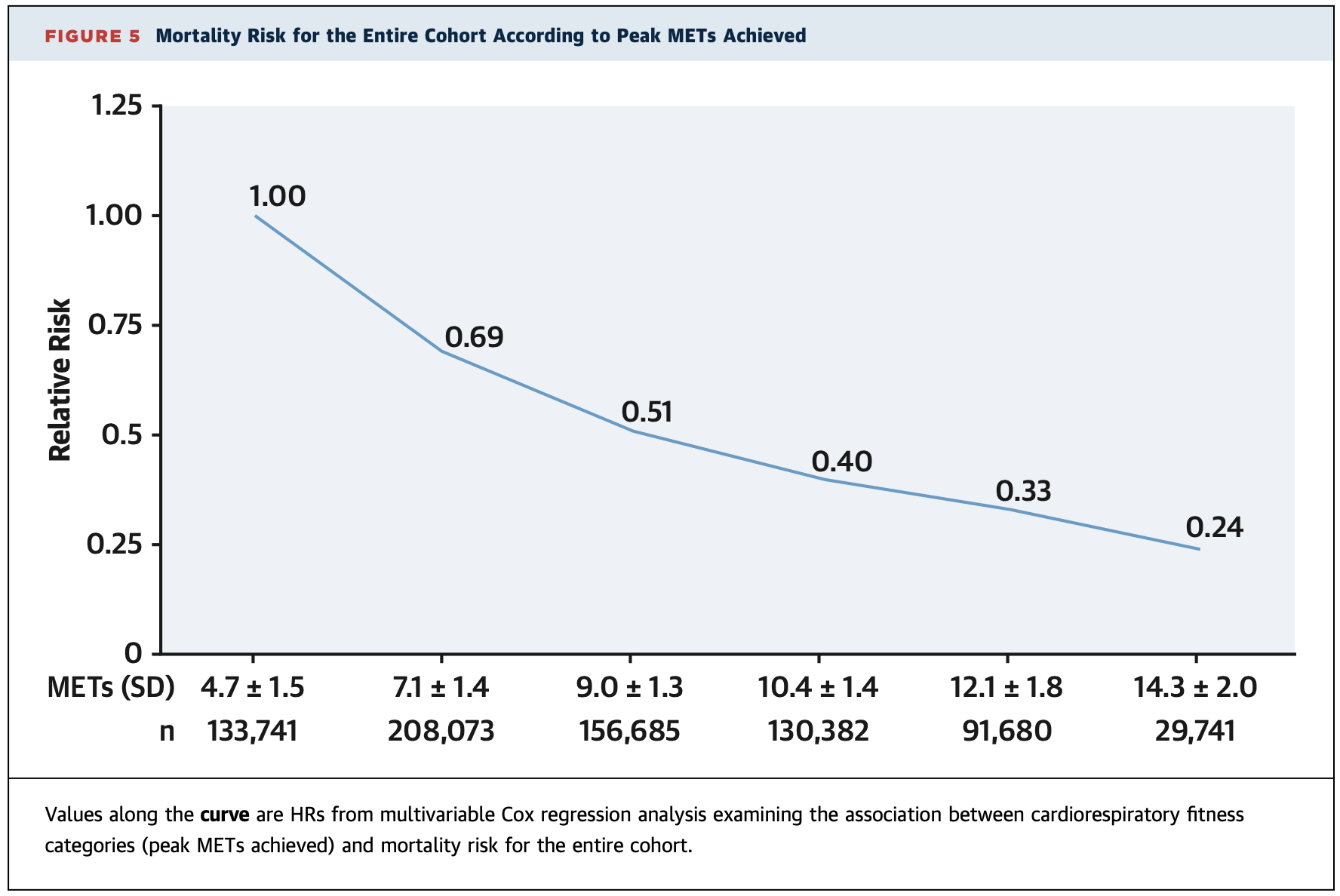

A 2022 large mortality study showed that for every increase in Vo2 Max of 3.5 mL/(kg.min), there is a reduction in risk of death between 5 & 10%.

Between the fittest group (~50 mL/(kg.min)+) and the least-fit (~15.75 mL/(kg.min)) there was a four-fold decrease in all-cause mortality.

In extensive studies like this, the researchers acknowledge that it is difficult to know whether a low Vo2 Max was the reason for the increased risk of all-cause mortality or if there is a compounding factor. i.e. people with a high Vo2 max also eat healthily, sleep for 8 hours and have better genetics.

Either way, the research is significant and compelling.

A missing element from many of these studies is the impact of a good Vo2 max on the quality of your life. Having a well-functioning cardiorespiratory system gives you a substantial functional reserve above the line of dependence and frailty. So that when you have the time to travel, enjoy your favourite activities and spend time with family, you also have the physical capacity to do so. Personally, maximising my retirement is a high priority.

Can you improve it?

Despite a natural decline with age, your Vo2 Max is highly trainable. As mentioned earlier, stroke volume is the primary adaption to endurance training related to Vo2 Max. Measurable improvements are possible in as little as six days due to changes in the walls of your heart, specifically the left ventricular.

A 30% increase in Vo2 Max after 12 weeks of training was demonstrated in both young and older participants. The effects were attributed to a higher rate of fat oxidation, which spares glycogen and allows more significant levels of exercise to be completed.

What should you do?

The Australian guidelines recommend 2.5 to 5 hours of moderate-intensity physical activity, which could be inferred as zone 2 training (remember from earlier).

As mentioned earlier, Zone 2 training is just one method of improving your Vo2 max. It can also be enhanced through high-intensity interval training or even resistance training.

We understand that exercise prescription is complex. Even when discussing it between colleagues, there is nuance and little consensus on the exact strategy as it depends on your training history, goals, equipment and availability.

But improving your Vo2 max can be simple if you are starting out. Here are three principles we preach at Absolute:

Something is better than nothing.

Build up gradually from wherever you are starting.

High volume is better than high intensity.

[Coming Soon] Click here to learn more about improving your cardiorespiratory system and Vo2 Max

Everyone can benefit from improving their Vo2 max and cardiorespiratory system. Doing so is entirely within your control, and the positive effects will be felt now and long into the future.

References:

Goodman, J. M., Liu, P. P., & Green, H. J. (2005). Left ventricular adaptations following short-term endurance training. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 98(2), 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00258.2004

Kokkinos, P., Faselis, C., Samuel, I. B. H., Pittaras, A., Doumas, M., Murphy, R., Heimall, M. S., Sui, X., Zhang, J., & Myers, J. (2022). Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality Risk Across the Spectra of Age, Race, and Sex. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 80(6), 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.031

Strasser, B., & Burtscher, M. (2018). Survival of the fittest: VO2max, a key predictor of longevity?. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition), 23(8), 1505–1516. https://doi.org/10.2741/4657

Murias, J. M., Kowalchuk, J. M., & Paterson, D. H. (2010). Time course and mechanisms of adaptations in cardiorespiratory fitness with endurance training in older and young men. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 108(3), 621–627. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01152.2009

Tanaka, H., & Seals, D. R. (2003). Invited Review: Dynamic exercise performance in Masters athletes: insight into the effects of primary human aging on physiological functional capacity. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 95(5), 2152–2162. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00320.2003